My wife and I recently took a trip to Niagara Falls, staying on the Canadian side. I also just finished reading Chaos: Making a New Science, by James Gleick. As I looked at the falls and the rushing Niagara River, thinking about all of that turbulence enhanced the experience.

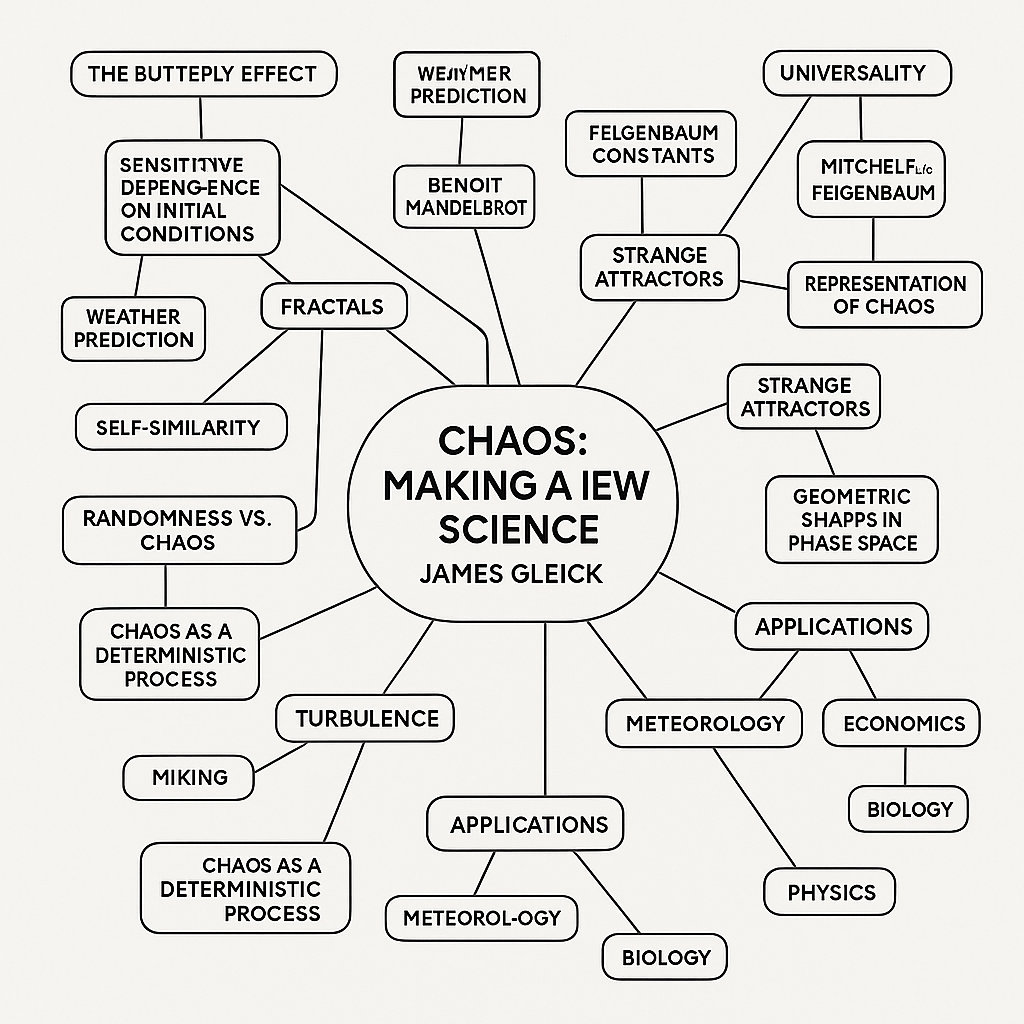

James Gleick’s Chaos: Making a New Science is a groundbreaking account of the emergence of chaos theory in the late 20th century. It traces how scientists in various fields began to recognize that deterministic systems could produce behavior so unpredictable that it appeared random—a profound shift in how we understand nature.

The Birth of Chaos Theory

Chaos theory grew out of dissatisfaction with traditional models in physics and mathematics, which often failed to account for the complexities of nature. In the 1960s, meteorologist Edward Lorenz discovered that small differences in initial conditions could lead to vastly different outcomes—a concept now known as the “butterfly effect.”

Key Concepts

Sensitive Dependence on Initial Conditions

Lorenz’s findings led to the realization that in many systems, slight measurement errors or rounding differences would make long-term prediction impossible. This insight revealed the limitations of classical determinism and laid the foundation for chaos theory.

Strange Attractors

Many chaotic systems do not wander aimlessly but instead follow a constrained, often fractal structure known as a “strange attractor.” These attractors can be visualized in phase space and reveal the hidden order in chaos.

Fractals and Self-Similarity

Benoît Mandelbrot’s work on fractals revealed geometric structures that are self-similar across scales. Fractals became central to visualizing chaotic systems and understanding irregularities in natural phenomena—from coastlines to clouds.

Universality and Feigenbaum Constants

Mitchell Feigenbaum discovered numerical constants that apply universally across systems undergoing period-doubling bifurcations on the route to chaos. This discovery brought a new level of mathematical rigor to the field.

Applications Across Disciplines

Chaos theory has transformed how scientists think in fields like:

- Meteorology: Improved understanding of the limits of long-term weather prediction.

- Biology: Insights into population dynamics, heart rhythms, and brain activity.

- Economics: Modeling nonlinear, sensitive systems such as financial markets.

- Physics: Understanding turbulence, fluid dynamics, and nonlinear systems.

Chaos vs. Randomness

A central theme in the book is the distinction between randomness and chaos. While chaotic systems appear random, they are actually deterministic, governed by underlying laws that produce complex outcomes from simple rules.

The Human Story

Gleick profiles many of the scientists who pioneered this field, including:

- Edward Lorenz – Meteorologist who discovered sensitive dependence on initial conditions.

- Benoît Mandelbrot – Mathematician who popularized fractals.

- Mitchell Feigenbaum – Physicist who identified universal constants in chaos.

These individuals faced skepticism from the scientific establishment, yet persevered and ultimately changed the direction of modern science.

Conclusion

Chaos captures the birth of a new paradigm in science—a shift from linear, reductionist thinking to a more holistic view that embraces complexity, unpredictability, and nonlinearity. Gleick’s narrative is not only a chronicle of scientific revolution but also a meditation on the nature of knowledge and the limits of human understanding.